Introduction

Recruiting a Workforce

The Experience of Discrimination

Directions for Further Learning

Introduction

The presence of migrants in Britain's labour force dates back centuries however the Second World War and its succeeding years saw them become a more significant component of the local and national workforce. The post-war period in Britain saw an acute labour shortage in many sectors and this was evident in Birmingham. The need for nurses was so acute at the Birmingham Infirmary that there was a very real prospect of having to close wards because of the shortage of nurses (Your Business, October 1947). In addition the city's fire brigade, police, salvage and public works departments were all suffering from a shortage of labour. Industrial and public sector employers were therefore keen to welcome migrant workers who helped satisfy the growing demand for unskilled labour in the city and allowed Birmingham industries and services to expand.

<return to top>

Recruiting a Workforce

To fulfil the growing post-war demand for labour, various companies and government departments, including British Rail and the National Health Service, operated recruitment schemes in Ireland, the Caribbean and South Asia. 'Jobs for thousands' were advertised in Caribbean newspapers and notices were displayed by agents in the towns and villages of the Punjab offering work in England (Black in Birmingham, 1987 p13). Birmingham firms ICI and Austin sent agents to recruit in the Republic of Ireland and the Transport Department placed advertisements in Irish newspapers and installed a permanent office in Dublin to recruit staff for its buses (Your Business, February 1951).

Granville Lodge remembers how, during wartime, he was recruited to the British armed forces whilst in Jamaica:

"The British Information Services had offices in Jamaica where they dished out propaganda stuff and I thought the war was glamorous as little boys do and I wrote to them and they sent me all the new pamphlets they had about bombers and soldiers and what have you and that caught my imagination. So, I joined the RAF, I think I put my age up about 2 years…" [MS 2255/2/85 pp2-3]

Britain's reliance on migrant labour had consequences for the countries migrants were leaving behind that were sometimes devastating. In 1965 the Jamaican Government issued an appeal to Jamaican nurses to return home since the dwindling numbers of nursing staff had led to the closure of a wing in the main hospital in Kingston (The Guardian, 24/11/1965).

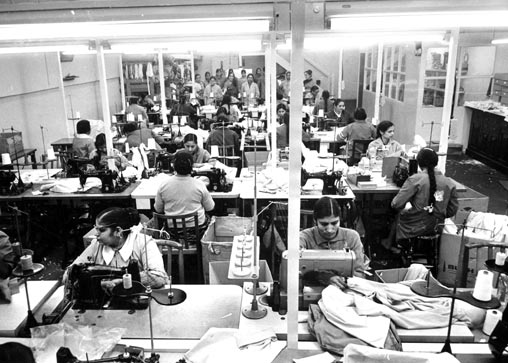

Whilst a significant number of migrants were skilled professionals, such as nurses, doctors and teachers, many were recruited to low paid, labour-intensive jobs with little security in the heavy industry, textile and service sectors. Many followed in the footsteps of other migrant groups who had come before them, such as the Poles and Ukrainians, who similarly undertook the jobs that the local population did not wish to do. The foundries and motor accessory plants such as Lucas's in Acocks Green took on large numbers of staff from Ireland, who were subsequently joined by workers from the Caribbean islands and India. Muriel Cowan, a former employee, remembers how the Irish and Caribbean workers had a lot in common because of their shared experience of being migrants in Britain and notes how the arrival of black people made life easier for the Irish:

"Well I think it was the Irish this and the Irish that and name calling and then when the blacks came in then it was a different kettle of fish, it took their mind off us, that’s the ways now we felt." [MS 2255/2/109 p17]

<return to top>

The Experience of Discrimination

Despite the initial welcome, discrimination was an experience that was common to many migrant workers. Whether they were professional or manual, skilled or unskilled, they were subjected to hostile working conditions, confined to the lower grades and roles, and paid less than their white colleagues (Sunday Times, 27/10/1968). Exploitation of black workers was common: in 'A Man's A Man' (1954:7) Henry Gunter highlights how in one Birmingham factory, 'coloured' workers had money extorted from them by a foreman for the privilege of working overtime. The Indian Workers Association also raised the issue of the exploitation of black workers in heavy industry highlighting the case of one small Birmingham firm in the mid 1960s which employed only 'coloured labour' and paid workers between £7 and £8 for a 50-60 hour week (The Times, 1/12/1965). Trade unions, despite their opposition to the oppression of working people, often resisted the employment of migrants and were complicit in their subjugation by forming agreements with management over issues such as quotas and dismissals. You can read more on this subject in the learning resources on Campaigns for Social Justice.

Huge barriers confronted people trying to enter employment in British institutions. The first black policemen and women were often subjected to barrages of abuse and threats in attempts to force them to abandon their ambitions. Birmingham's first black policeman, a Trinidadian called Ralph Ramadar, found swastikas painted on the front door and wall of his house in Leamington Spa (Birmingham Post, ?1966) and the first black policewoman in Britain received dozens of threatening letters prior to beginning work in Croydon (Daily Sketch, 29/4/1968).

The experience of racial discrimination at work could be distressing, particularly in environments where migrants were the only member of a visible minority group. For Evelyn, who came to Britain from Jamaica in 1964, such an experience eventually led her to leave work:

"… them give me the hardest work to do and less money… no money at all. Well, there was a white woman, I don’t remember her name now, she says to me, “Eve, never mind, you will get over.” Them says, “where the tail?” “I haven’t got a tail.” A monkey, them says, “Miss Monkey, still haven’t got a tail?” Them says, “where is the tail?” I says, “well, I can’t show you no tail because I haven’t got one,” but they still call me monkey."

[MS 2255/2/24 p1]

Many found that the skills and qualifications they had gained overseas were not recognised despite being educated through a system which was by all accounts 'British.' Jossett Lynch, who trained as a teacher in Jamaica and taught juniors for three years before coming to Britain was told by the Education Department in Birmingham that she could not teach without further training:

"… unfortunately I got a reply back saying I could not teach in this country until… unless I am trained because the standard of education in Jamaica cannot be equated with that in England, which of course is not true because the laws are the same, the education system is the same…" [MS 2255/2/12 p10]

In addition to the disillusionment facing many highly qualified migrants trying to find work in Britain, the discriminatory attitude of some employers against the employment of 'coloured' labour led to one newspaper to observe that "it may be easier for a coloured person to get into university or the Kingdom of Heaven than into a typing pool" (The Observer, 3/5/1964).

Legislation, in the form of the 1968 the Race Relations Act, finally enabled some ground to be made in countering the negative experiences of black and other migrant workers as discrimination in employment became illegal. Despite the legacy of inequality that exists in the employment of people from black and minority ethnic groups in the present day, it is important to recognise that the many pioneers who struggled to work over the decades established a black presence across all industries and sectors without which the development of local and national systems and infrastructure in Britain would have been limited.

<return to top>

Directions for Further Learning

The relationship between black workers and the unions was an important aspect of migrant working lives. You can read about aspects of this relationship in Campaigns for Social Justice and in the exhibition Birmingham and the Grunwick dispute 1976-1978.

Oral histories provide an insight into migrant experiences of employment. One example that you might wish to read or listen to is the oral history interview with Avtar Jouhl of the Indian Workers Association (GB), who actively campaigned for migrant workers' rights during the 1960s and 70s, which can be found in Birmingham City Archives. The interview, in which Jouhl recounts his experiences of activism and life in the foundries, is a valuable source of knowledge that is not contained in traditional historical texts.

<return to top>

Author: Sarah Dar

Main Image: Photograph by Paul Hill [City Archives: MS 2294]

<return to top>

|